What is it that makes a particular research have an impact on society beyond the strictly academic and which is truly transformative? Can a whole series of actions be planned in the way that one follows a cooking recipe which leads directly to the desired social impact? Unfortunately, the answer is no. The impact is multifactorial and depends on so many different elements and actors that it is difficult to establish a formula to guarantee it.

However, having said that, the fact that there is research which has a particular social impact does not mean that it is a totally random phenomenon and that there is no way of predicting, facilitating or promoting it. Years ago, from the Research Assessment group at the Agency for Health Quality and Assessment of Catalonia (AQuAS), and with the help and complicity of the International School on Research Impact Assessment, ISRIA, we identified a series of facilitators with regards the impact of research.

A fundamental facilitator is people, and the values, culture and capacity of leadership they have. Two identical results of research can have different impacts if the capacity of leadership, drive and will to get beyond academic impact is different. But this is still not enough. The strategy, organisation, collaborations and openness that institutions have will be a great facilitator or barrier for the researchers that have carried out the research.

Finally, both people and institutions will need two indispensable elements in order to aspire to having an impact: on the one hand, a close and effective communication with the different social actors that can play a role in transferring the results of research, and on the other, an approach focused on the participation of all these key players.

To paraphrase Confucius when he said “explain it to me and I will forget, show me and maybe I will remember, involve me and I will understand”, it is all about involving all the necessary actors to bring about a real change and make research transformative.

It is in this context that SARIS (Catalan acronym) came into being, the Assessment System of Research and Innovation in Health. It is a strategic tool which emerged from the PERIS (Strategic Plan for Research and Innovation in Health 2016-2020) with the aim of assessing the research carried out in health in Catalonia from the perspective of always wanting to facilitate and influence so that it has an impact beyond academia. To do this, the motivation and involvement of actors has been defined as a key factor for its development.

Last November, we started a series of participative sessions with nurses who were selected from the PERIS 2017 call in which a line of intensification of nursing professionals was financed.

It is important to emphasise that launching this line with nursing research makes full sense for three reasons: on the one hand, one of the thematic priorities of the PERIS is clearly that of “the development of clinical and translational research which facilitates the growth of scientific and technological knowledge, putting special emphasis on primary care agents and research in nursing”. In addition, the PERIS 2017 nursing fund has been the first to come to an end and it was appropriate to address ourselves to them first and foremost.

Last but not least, the conditions in which nursing research is carried out, with patients and their recovery as its central goal, makes it especially appropriate to ensure that this research has a direct impact on health. Hence, it is important that the research done in nursing be capable of demonstrating the impact that this group of professionals has because it can give it a comparative advantage with regards other biomedical disciplines. Indeed, nursing research is intrinsically translational.

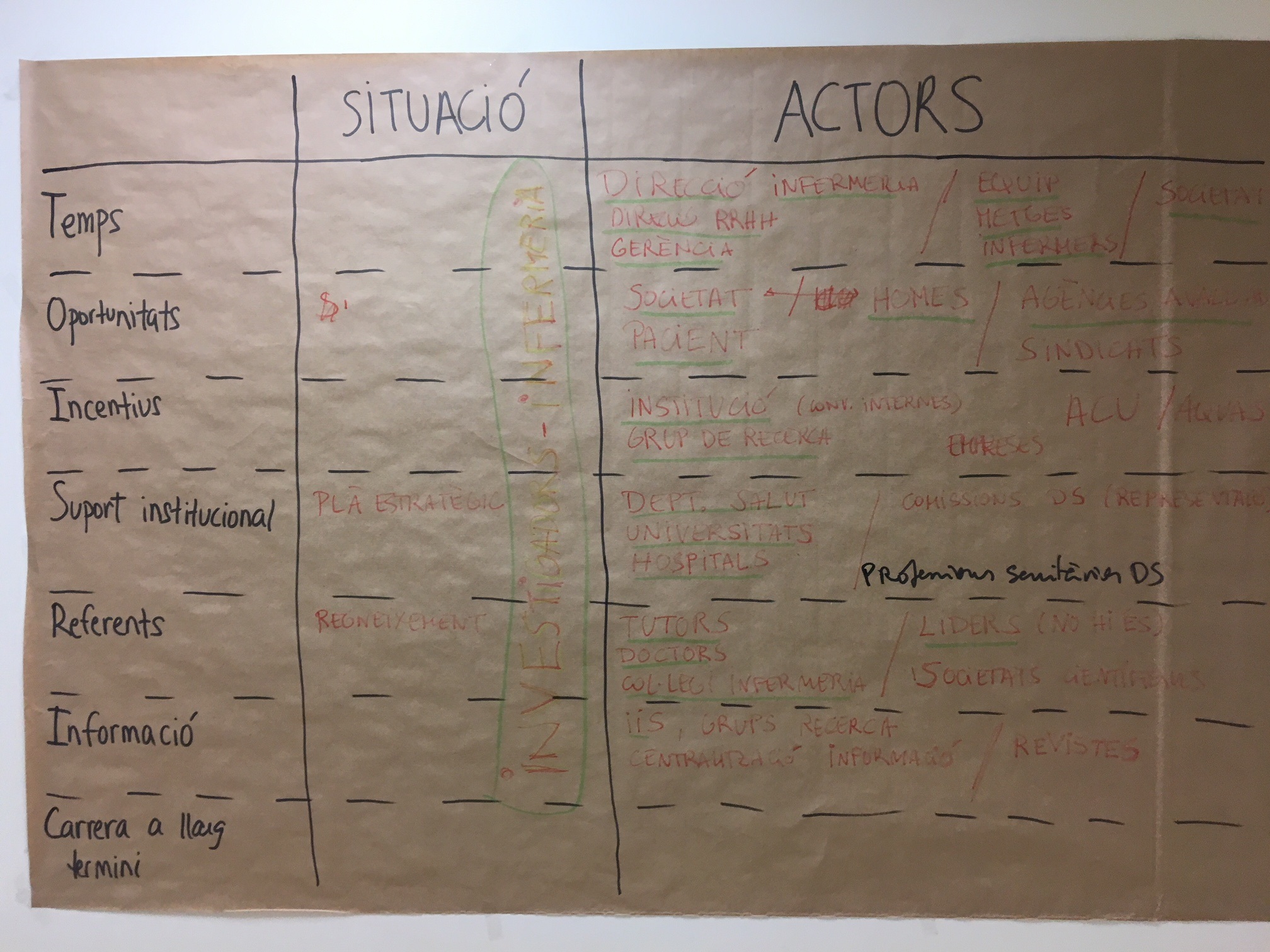

Therefore, the first session centred on identifying the influential actors and in empowering the nurse to carry out an effective communication which amplifies the productive interactions needed to transform the results obtained into benefits for a better and improved health for patients.

We would like to express our deepest gratitude to the nurses for their participation (readiness and motivation) who attended of their own free will and in their time off work ensuring thus that the session was a success. This demonstrates that from the AQuAS we have leverage to give support to those researchers who are motivated to driving the impact of their research.

At present, we are preparing other sessions that will enable mutual learning between researchers and the assessment agents at the AQuAS.

Post written by Núria Radó Trilla (@nuriarado).

Jornada SARIS: Participación en recerca Barcelona, April 4th 2018.