An article in JAMA has recently been published presenting the first smart watch approved by the FDA to predict epileptic seizures. It is called Embrace, a connected device which detects seizures linked to movement and electric fluctuations in the skin of a person and sends an alert so they can receive medical attention.

Last February, the Mobile World Congress was held in Barcelona. Among the different activities to be highlighted which are organised around this congress there is one called 4 Years From Now (#4YFN18), the part of the Mobile which connects companies, investors and institutions with each other to encourage collaboration in developing different ideas, business models and technological solutions.

Last February, the Mobile World Congress was held in Barcelona. Among the different activities to be highlighted which are organised around this congress there is one called 4 Years From Now (#4YFN18), the part of the Mobile which connects companies, investors and institutions with each other to encourage collaboration in developing different ideas, business models and technological solutions.

The Digital Health & Wellness Summit 2018, organised by 4YFN Connecting Startups, the Mobile World Capital Barcelona and the Mobile World Congress with the collaboration of ECHAlliance, the European Connected Health Alliance, is the meeting point of technological and health issues. This year, among others, Neil Gomes, Maria Salido and Elena Torrente participated.

Neil Gomes from the Thomas Jefferson University of the USA pointed out that one of the challenges in mHealth is facilitating feedback between patients and health professionals.

Maria Salido, co-founder and CEO of the health app, SocialDiabetes, raised key issues for success with health apps: regulation + industry + users. And in particular, she highlighted the importance of the final users. An article published in The Economist was much commented on here with a provocative title:

Elena Torrente, Digital Health Coordinator at DKV, commented on Digital Doctor, a health app that incorporates a detector of symptoms and a tool to request a doctor’s appointment. She pointed out that there were more women than men in the user profile of the app.

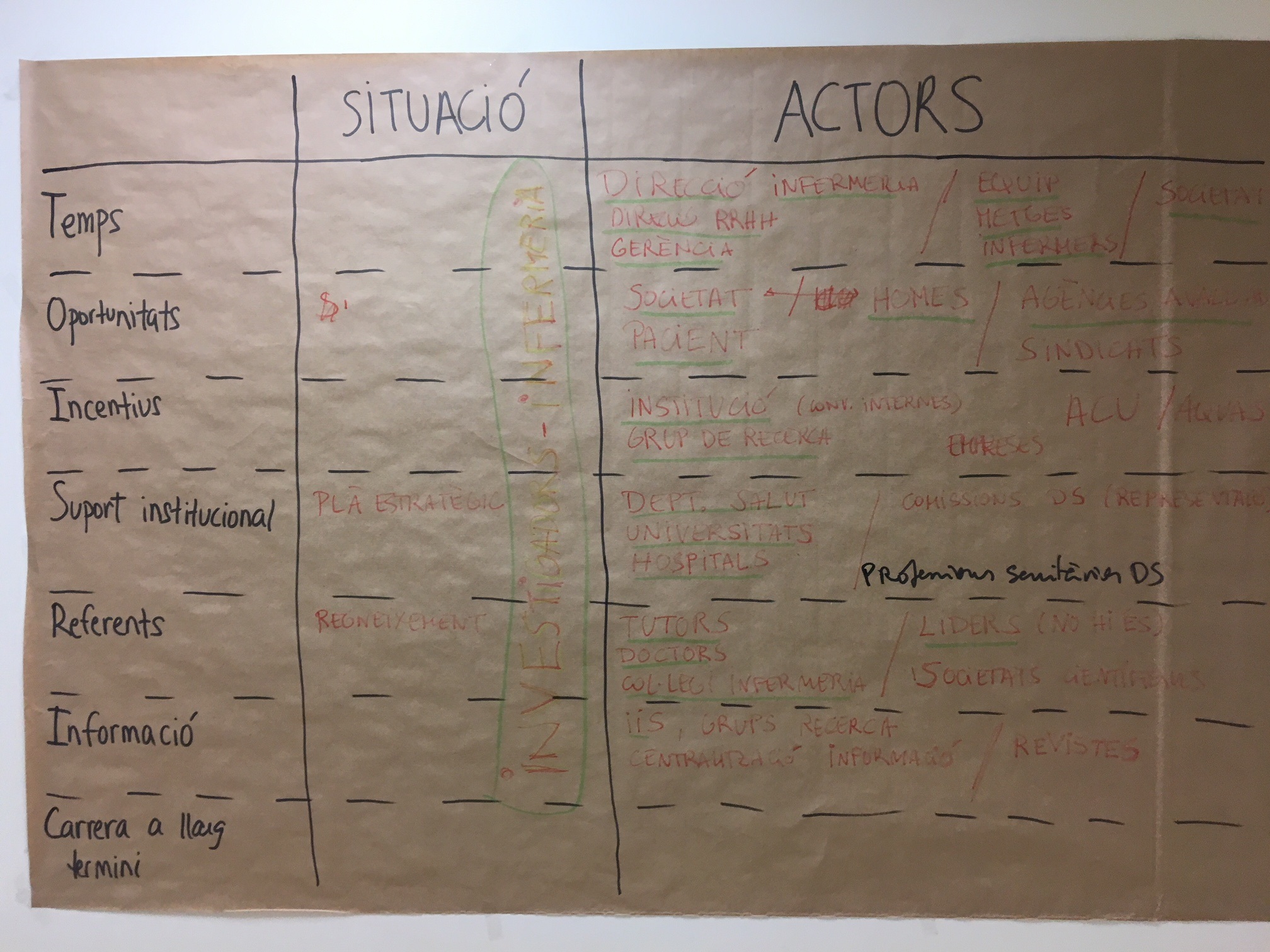

In general, there was consensus on the fact that prior to developing an app, an analysis to identify needs must be done. That is, the first step should be to detect the needs of a user and then, based on the mapping of these needs, the moment would come to develop technological solutions.

The content of all these presentations is available and you can also read a compilation of the main ideas that were highlighted here and here.

Despite it not being the main subject of their presentations, in the follow up debate the need and convenience of assessment was brought up. At present, there are already 320,000 health apps on the market. But,… How are they assessed? Who does this? With what criteria? Can we already talk about the safe prescription of health apps?

We close the circle once again with the conceptual framework of mHealth Assessment published in JMIR mHealth and uHealth with which the Agency for Health Quality and Assessment of Catalonia (AQuAS) provides the culture of assessment to the everyday reality in which we find ourselves (in 2016 it was published in the first quartile, in the categories “Health Care Sciences & Services” and “Medical Informatics”, respectively, in the Journal Citation Reports). There are an increasing number of health apps and the debate concerning their assessment remains open.

Post written by Marta Millaret (@MartaMillaret).